I'm Not Sure What to Call This, But It Began as an Epstein Reaction Article

And then got a little darker.

Prefatory Note #1: A principle, until it is tested, is just a hypothesis.

*************

Prefatory Note #2: The reason to humanize the inhuman, relate the unrelatable, and imagine the unimaginable is not to render them acceptable, but preventable — to remember that, just as we can do extraordinary good, we can do extraordinary evil and call — and maybe believe — it good.

*************

Prefatory Note #3: I am not a reporter, nor an investigative journalist, nor an oracle, nor a conspiracist, nor more familiar than average with the particulars of the Epstein crimes and controversy. As I write, I often wonder — sincerely — what I can add to the conversation — what a random lawyer typing on his laptop in Utah while nursing a Dr. Pepper Zero - Blackberry (“For those of you who apparently like the taste of cough syrup, but wish it had caffeine and bubbles”) can tell you that better writers and thinkers can’t, or won’t. And then I shrug, take another sip, realize the can is now empty, glare at it as if it wronged me, shrug again, feel thirstier than I did before the sip, and then write about what interests me, hoping that, if I write honestly, what I write will interest you too.

*************

In 1963, German-American historian, philosopher, and political theorist Hannah Arendt — a Jewish woman who was imprisoned by the Gestapo in 1933 for research into antisemitism; fled to France, only to be detained again after the Germans invaded in 1940; and escaped and made her way to the United States in 1941 — published Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, her analysis of the trial in Israel of Nazi official and SS officer Adolf Eichmann, whom Mossad agents had captured in 1960 in Argentina. Today, the book is most famous for Arendt’s observation that Eichmann, a principal organizer of the Holocaust, key attendee at the Wannsee Conference where the Nazi hierarchy discussed the implementation of the Final Solution to the Jewish Question, and the man who, with evident satisfaction, managed the logistics of renditioning millions of European Jews to ghettos and extermination camps across the Nazi-controlled portion of Europe, was, in her view, not truly evil, at least not as we might expect him to be.

Eichmann was less deliberately wicked than conformist, a joiner who obeyed the rules of — and sought advancement within — the context in which he found himself. To crib from management consultant Douglas Hubbard — “never attribute to malice or stupidity that which can be explained by moderately rational individuals following incentives in a complex system” — he was a moderately rational individual following incentives in a complex, horrifying system. He was a drone: he was not Hitler, nor Heydrich, nor Himmler. He followed orders; he had a job, and he tried to do it well. In a sense, the Holocaust wasn’t his idea — he just went along with it.

A Hungarian Jewish mother and her children at Auschwitz. Virtually all children and mothers of small children were immediately sent to the gas chambers upon arrival at the camp.

Arendt’s assessment of Eichmann remains controversial: there are many who have argued there is compelling evidence to believe Eichmann was every bit as evil as you’d think him to be based on his crimes, and his anodyne explanations for his crimes mirrored those of the extermination camp leaders who personally carried out, often with marked, gratuitous cruelty, some of the worst atrocities in recorded history. But her stripped-down thesis holds: that ordinary people, or people who have the capacity for ordinariness, can, under the wrong circumstances, commit acts of extraordinary evil.

Does any other explanation make sense? The late Professor Roger W. Smith, a scholar of genocide who spent the bulk of his teaching career at William & Mary, wrote that the 20th century was “an age of genocide in which 60 million [emphasis added] men, women, and children, coming from many different races, religions, ethnic groups, nationalities, and social classes, and coming from many different countries, on most of the continents of the earth, have had their lives taken because the state thought this desirable.”

The “state” to which Professor Smith refers is not an artificial, inanimate, self-contained entity — it is composed of humans subject to something approximating the full gamut of human yearnings and limitations, and its orders and wishes are carried out by other humans subject to the full gamut of human yearnings and limitations.

The Holocaust was not foreordained, and “genocidal intent” is not a hereditary trait unique to certain races: the ethnic Germans were no more genetically predisposed to commit genocide than Jews, Slavs, and Romani were to be their victims, or the relatively diverse Ottomans were to murder their Armenian countrymen, or Russians were to become communists, or the French were to encore their heroic performance in World War I (the part we forget) with an almost immediate surrender in World War II (the part we remember). The worst crimes in human history were committed by people — people possessed of free will and exercising it to do the unthinkable.

So what does it take for moderately rational individuals — millions of them — following incentives in complex systems to embrace murder on a scale sufficient to wipe out nearly the entire current population of France or the United Kingdom?

Professor Smith goes on:

“Genocide must be legitimated by tradition, culture, or ideology; sanctions for mass murder must be given by those in authority; the forces of destruction have to be mobilized and directed; and the whole process has to be rationalized so that it makes sense to the perpetrators and their accomplices. Victims, however else they may differ, will be vulnerable to attack and will be perceived as lying outside the universe of moral obligation. They will be dehumanized: ‘Cargo, cargo’ is the way [Nazi extermination camp commandant] Franz Stangl described his victims at Treblinka; ‘Guayaki,’ a term meaning ‘rabid rat,’ is how the Paraguayans refer to the Aché Indians. They will be viewed not as individuals but only as members of a despised group, blamed for their own destruction, and held accountable in terms of the ancient notion of collective and ineradicable guilt.”

In short, the genociders — the everyday, normal people pulling the literal and metaphorical triggers — must enter a bizarro world where, for as long as the genocide continues, and as long as the state which ordered it exists and can reward its agents, they can believe what they are doing is right in and of itself, or a necessary means to a worthy end. Their victims are Untermenschen deserving of their fate, or not worthy of a better one. The process of legitimization can be self-perpetuating: our need to rationalize our actions is innate and intense, and our ability to do so almost unlimited. Should the justification provided by the state not be sufficient, the genociders can invent one that is: “it was God’s will, we were defending ourselves, they had it coming.”

And then, when it all comes crashing down, there is “the refusal to accept responsibility….[T]he sharp division of labor fragments the act of destruction—those who decide to commit genocide, those who organize it, and those who carry it out are not the same persons; no one, therefore, accepts responsibility for the final result….[B]ecause of the hierarchical structure of the organization, everyone can insist, not insincerely, that they were only obeying orders. If organization, communications, transportation, and various new implements of violence (among them the gas chambers) have played central roles in the technology of genocide, their capacity to reduce moral awareness has also been important.”

*************

Now, you might be wondering how I began thinking about an underage sex trafficking ring — or, if not a full-fledged ring, a shockingly prolific Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell-run scheme that produced “over one thousand victims” according to the FBI — and ended up writing about genocide.

I am one of the world’s worst conspiracy theorists. Part of that can probably be attributed to a natural inclination to credulously shill for the government and establishment, but if you were to ask me to give a more thoughtful explanation as to why I insist on being such a buzzkill, I would say (not literally — I’d never be clever enough on the spot) I believe in the value of a number of problem-solving principles which, in combination, and whether used consciously or unconsciously, can really take the knees out of a lively discussion about the evils of political opponents or the global cabal holding the strings from which we marionettes unwittingly dangle and flail:

Occam’s Razor — the explanation which requires the fewest unjustified assumptions is usually best;

Hitchens’ Razor — that which can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence;

Alder’s Razor — if something cannot be settled by experiment or observation, then it is not worthy of debate (plus my corollary: if neither participant in a conversation is willing to perform the necessary experiments or observations or believe the results of those performed by others, it is also not worthy of debate);

Hanlon’s Razor — never attribute to malice that which can be explained by stupidity; and

Douglas Hubbard’s corollary to Hanlon’s Razor — never attribute to malice or stupidity that which can be explained by moderately rational individuals following incentives in a complex system.

It’s not that I believe nothing bad ever happens or that governments and powerful corporations always tell the truth — far from it. Believing that would require a Herculean feat of selective memory. But I do believe, as a general rule, that (1) the explanation for the crime and coverup is often much, much more normal and relatable — more banal — than you’d think; and (2) there is danger in thinking otherwise.

There is danger in otherizing the corrupt and ostensibly wicked and, in so otherizing, not understanding our own vulnerability, the conditions under which we might do the exact same thing, either as participants or bystanders. The difference between the rank-and-file Germans who committed genocide and the Americans who didn’t was in the conditions — the leaders, the opportunities, the pressures — not the blood, and perhaps not even in their stated principles. A principle, until it is tested, is just a hypothesis, and there is little more human than prioritizing the end over the means and, through after-the-fact mental gymnastics, convincing ourselves we’ve done the exact opposite.

I don’t know how the Epstein saga will end. The FBI claimed a “systematic review” of “investigative holdings relating to…Epstein…revealed no incriminating ‘client list.’” Agents “did not uncover evidence that could predicate an investigation against uncharged third parties[,]” and, contrary to the suspicions of a great many, “Jeffrey Epstein committed suicide in his cell at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York City[.]”

The FBI’s position doesn’t square with that of Julie K. Brown of the Miami Herald, the investigative journalist responsible for making Epstein a household name and eventually bringing him down. Brown recently spoke to Ross Douthat, conservative columnist for The New York Times, on his podcast, Interesting Times. She expressed genuine confusion at the government’s insistence that the case is closed, arguing that — as Douthat put it — “there are other people out there who are guilty of Epstein’s crimes, who should face justice and haven’t”:

Yeah, let me be clear: Epstein did not do this all by himself. He barely tied his shoes by himself. He had butlers and assistants doing everything for him, including the compiling of his contact lists, his musical playlists. He had people doing that for him. His computers — he had lots of people helping him. So he did not do this alone. There were other people helping him. And there were other men who sent some of these women too.

The Wall Street Journal reported that, in May, Attorney General Pam Bondi told President Donald Trump that his name appears multiple times in the “‘truckload’ of documents” that comprise the so-called Epstein files. That his name is in the files does not mean he is guilty of any Epstein-related crimes — Trump was personal, oft-photographed friends with Epstein for 15 years before a falling out around 2004, approximately six years after Epstein purchased his island, and it’s hard to imagine how he would have avoided inclusion in a comprehensive investigative file — but it would explain why Trump, as aware as anyone that the court of public opinion and court of law don’t share the same address or rulebook, tried to divert the public's attention to other subjects with a performance bound to someday be included in the “How to Act So Obviously Suspicious It Almost Makes You Seem Unsuspicious” Hall of Fame.

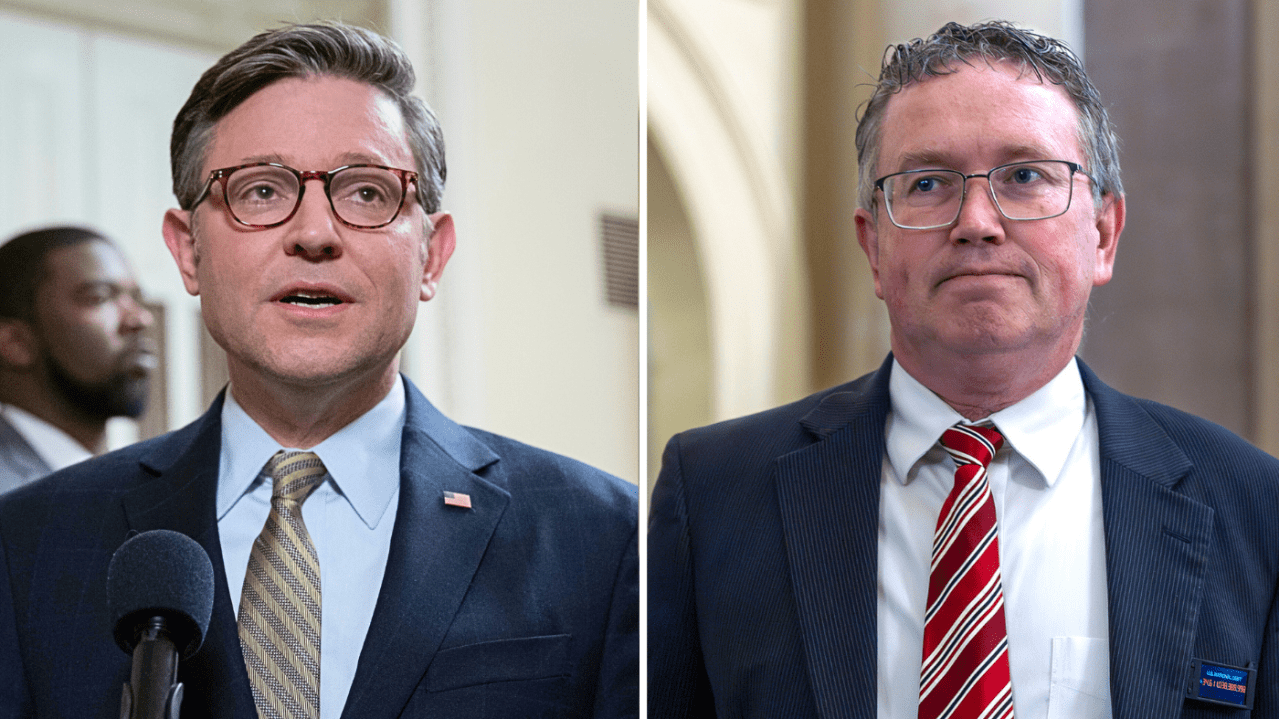

Then, in a brilliant move I’m sure mollified Trump’s millions of supporters who count (1) uncovering government corruption and (2) stopping sex trafficking among their top priorities — and I could give you a dozen names of personal friends and acquaintances without even opening Facebook — House Speaker Mike Johnson canceled votes scheduled for the following day in order to send House members home for August recess a day early and avoid a vote on a bipartisan resolution that would compel the Department of Justice to release the Epstein files; when Johnson canceled the votes, the resolution had 11 Republicans and 9 Democrats as co-sponsors.

Johnson has been active in his defense of the president, arguing on X that “Republicans won’t be lectured on ‘transparency’ by the same Democrats who orchestrated [the cover-up of] Biden’s obvious mental and physical decline.” Representative Thomas Massie of Kentucky, a libertarian-leaning Republican gadfly and resolution co-sponsor who gains Democratic fans every time he opposes the president, then loses them when they realize he’s generally more conservative than other House Republicans, not less, responded: “[W]hy are you running cover for an underage sex trafficking ring and pretending this is a partisan issue? MAGA voted for this.”

*************

Wherever we find ourselves some months down the road, I fear we’ll end up doing exactly what we’ve done a thousand times before: wholeheartedly condemning anyone whose fall won’t hurt us, and excusing the actions of those whose fall would.

Beginning no later than President Bill Clinton’s impeachment for lying under oath about his affair with 22-year-old Monica Lewinsky, Republicans claimed the moral high ground; they were the party of principle, and Democrats dissolute in word and deed.

Then along came Trump. Donald Trump is not a beacon of Puritan morality, and might have gone beyond the hedonistic excesses of the famously licentious, but discreet, Victorian upper class (Winston Churchill’s mother, for example, carried on long, overlapping affairs with a large coterie of notable lovers, including the heavy-lidded philanderer who would later rule the British Empire as King Edward VII). Even if you assume each of the more than two dozen sexual misconduct allegations against him is false, and that the Access Hollywood tape and bawdy Howard Stern interviews were nothing more than “locker room talk” and ribald attempts to sell the image of Trump the playboy, the president is a thrice-married billionaire credibly alleged to have cheated on all three of his model wives. His private life was — with his approval — gossip magazine fodder for decades before he made any serious attempt to run for political office, and not because he was famously faithful and stalwart as a husband. He is not, by virtually any traditional measure, a good man, and he isn’t John F. Kennedy, who managed to keep his lechery largely under wraps while projecting a wholesome image to the public.

But he won. He won the Republican primary in 2016, then the general election (albeit not the popular vote); then, after four years as a sort of opposition leader in exile, he won again. He won not just with the populist conservatives he more obviously represented, but religious conservatives who it seemed should have abhorred — and maybe did abhor — everything about him as a man.

“I don’t give a s— about Trump getting handsy with somebody 20 years ago. I want someone who will close the border, which he has. I want someone who will keep boys out of my daughter’s sports, which he has. I want someone who will stand up to the insane DEI policies so that white kids will stop hearing in school that they’re born with some original sin from which they cannot recover, which he has.”

Megyn Kelly, The Interview, March 29, 2025

Kelly’s position is more principled than it might appear at first blush: good character is preferable to bad, but a politician’s character is secondary in important to his or her ability to effectuate an agenda which will help (or hurt) tens of millions of people. That’s not an unreasonable view, and I think it’s likely a very, very common one.

And Republicans aren’t alone in making something of a Faustian bargain.

In late May, not long after Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson released Original Sin: President Biden’s Decline, Its Cover-Up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again, which, per the title, is about Biden’s decline, its cover-up, and his disastrous choice to run again, and Biden announced his diagnosis with metastatic prostate cancer, a close friend and Republican Trump supporter asked me if I was ready to call it quits on the untrustworthy, manipulative, two-faced, feckless Democrats (his implication, if not his words) and come over to the team that didn’t try, for little reason beyond its leader’s considerable ego and his inner sanctum’s delusions and concern with preserving their access to power, to convince the American people that a rapidly aging octogenarian was the best available option to serve as the world’s most powerful person until January 2029, and to mislead them regarding his current capabilities.

The answer was easy — respectfully, no — but the question was telling. When Republicans look at Democrats, they don’t see principled Americans who happen to believe in a more economically active federal government and are standing on the right side of history with respect to our debauched president: they see sanctimonious moralizers who (1) chased Al Franken from office but continue to run Bill Clinton out as a Democratic National Convention headliner and beloved talk show guest despite Clinton’s actions being far worse, and (2) defiantly supported a man who looked like he drank from the wrong grail in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, then shifted to his vice president overnight as if there could hardly be anything more natural. In other words, they see people who oppose Trump, but wouldn’t hesitate to support a Trumpian Democrat.

For what it’s worth, I’m not claiming to judge any of you from above: I voted for Harris in November and would have voted for any number of less qualified nominees, including Biden, dead or alive; I consider every Bill Clinton DNC speech and talk show appearance appointment viewing — he’s the most charismatic person I think I’ve ever seen.

The problem with this isn’t necessarily that we’re supporting people who fall well, well short of some mutually agreeable standard of personal behavior, but that we think we’re not; or, in the alternative, that we’ve decided the best way forward is political nihilism — broad agreement that character genuinely doesn’t matter, and that being honest and open about that is good.

*************

Let me end with this: our goal with Epstein, as with misdeeds much more and less severe, should not just be to discover the truth, right wrongs, and, if needed, punish those deserving of it, but to do what we can to ensure what is wrong is neither excused nor repeated.

Perhaps people like Hitler, and Himmler, and Epstein are genuinely different — aliens whose thoughts, wishes, and actions are so foreign to our own that we can gain nothing by seeking to understand them.

But for every person who is genuinely, unfeelingly wicked, there are many, many more who are not; who, under different conditions, would be good, would do good; who, even in doing evil, go to great lengths to convince themselves and others they are still good.

And maybe that’s the silver lining of humanity’s worst crimes and the warning in its grandest achievements: we are capable of both. One complex system can take moderately rational individuals, subject them to certain incentives, and produce banal evil; another can take equally rational individuals, subject them to other incentives, and produce banal good.

America, writ large, is one heck of a lot better than the Third Reich and a pervert’s private island in the Caribbean, but our incentives aren’t perfect. In politics and elsewhere, it can and often does pay to be cruel, and unkind, and quick to judgment, and unforgiving, and hypocritical. Is that helpful, and what are the chances it magically changes?

So, without getting too preachy, I hope we do what we can to (1) create conditions and systems that incentivize and reward good and (2) steel ourselves to be good even in the absence of such conditions: in other words, to ensure that our principles, when tested, hold.

Addendum

“Seriously though, we’ve heard a lot about extremism recently: a nastier, harsher atmosphere everywhere, more abuse and bother-boy behavior, less friendliness, tolerance, and respect for opponents. Alright, but what we never hear about extremism is its advantages. Well, the biggest advantage of extremism is that it makes you feel GOOD—because it provides you with enemies.

Let me explain: the great thing about having enemies is that you can pretend that all the badness in the whole world is in your enemies, and all the goodness in the whole world is in you. Attractive, isn’t it? So, if you have a lot of anger and resentment in you anyway, and you therefore enjoy abusing people, then you can pretend that you’re only doing it because these enemies of yours are such very bad persons. And that if it wasn’t for them, you’d actually be good-natured, courteous, and rational all the time.

So, if you want to feel good, become an extremist.

Okay: now you have a choice. If you join the hard left, they’ll give you their list of authorized enemies—almost all kinds of authority, especially the police, the City, Americans, judges, multinational corporations, public schools, furriers, newspaper owners, fox-hunters, generals, class traitors, and, of course, moderates.

Or, if you’d rather be an extremist on the hard right, no problem, fine, you still get a lovely list of enemies, only a different one: noisy minority groups, unions, Russia, weirdos, demonstrators, welfare sponges, meddlesome clergy, peaceniks, the BBC, strikers, social workers, Communists, and, of course, moderates—and upstart actors.

Now, once you’re armed with one of these super lists of enemies, you can be as nasty as you like and yet feel your behavior is morally justified. So, you can strut around abusing people and tell them you could eat them for breakfast and still think of yourself as a champion of the truth—a fighter for the greater good—and not the rather sad, paranoid schizoid that you really are.”

Mr. Hagen,

Much to think about. But this one caught my eye. Bill Clinton and oaths.

"I Bill Clinton do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of president of the Unired States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States." And I am sure that he made some oath upon marrying Hillary that we all have, to be faithful to her. How can we trust that once an oath is broken the practice will not become easier and easier. This applies to everyone.

This is why the example of George Washington's character is so important to our nation. At least subsequent presidents tried to hide their transgressions against the Constitution. (until recently) Now we live in an era of shamelessnes. This may sound too simple but to have principles, virtue, and character enable us to recognize evil and not have to reason out a new course of action every time we encounter a moral dilemma.

You know, every time I encounter someone on the street that wants me to buy something he's selling out of his trunk I simply say "no." I don’t have to think about it. And the same goes for the oath I took in front of God and all those loved ones on my wedding day.

How hard is it to forego the oath and office if you have no intention of keeping it. Take care.

This is a fabulous piece of thinking and writing. May we all reflect on the pressures attendant with hard realities and resolve to choose the right, kind, good, and morally defensible option when faced with a choice.